New York State Garnishment Laws

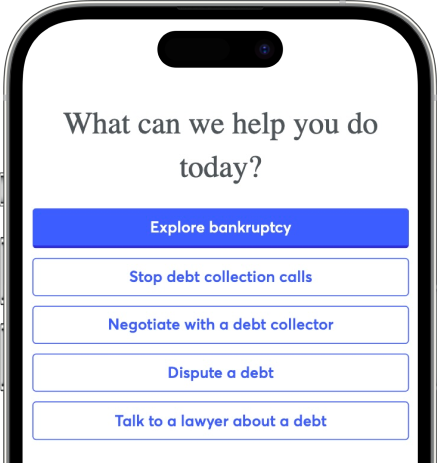

Upsolve is a nonprofit that helps you get out of debt with free debt relief tools and education. Featured in Forbes 4x and funded by institutions like Harvard University so we'll never ask you for a credit card. Get debt help.

Most creditors must get a court order to garnish your wages if you live in New York. Two exceptions are garnishments for public debts — like past-due taxes — and family debts, like child support. The law limits how much of your weekly earnings a creditor can take through wage garnishment. These limits vary based on the minimum wage where you live. Finally, an employer can’t fire you because you have a wage garnishment order against you.

Written by Attorney Paige Hooper.

Updated July 25, 2023

Wage garnishment is stressful. You may wonder whether you’ll be able to support yourself and your family, or even whether you’ll lose your job. Fortunately, New York and federal laws limit how much of your check a creditor can garnish. They also provide other protections for employees facing wage garnishments. This article covers how wage garnishments work in the Empire State, what protections are available, and how you can stop wage garnishment in New York.

Wage Garnishment in New York

In New York, most creditors can’t garnish your wages unless they have a money judgment against you. To get a judgment, a creditor must first file a lawsuit against you. If they present evidence that you owe them money, the judge will order you to pay. This order is called a judgment. If you don’t answer the lawsuit or don’t show up in court, the creditor can still get a default judgment against you. Most debt collection lawsuits in New York lead to default judgments.

A creditor who has a judgment against you is called a “judgment creditor.” Court documents might refer to you as the “judgment debtor.” The amount you’re ordered to pay is called the “judgment debt.” A judgment creditor can ask the judge to issue an income execution. An income execution is a court order requiring your employer to withhold money from your paychecks to pay the judgment debt.

New York’s consumer protection laws limit how much can be taken from each check, based on the type of debt involved. These laws and limits only apply to wages you earn as an employee. They don’t apply to income you earn as a freelancer or independent contractor. Once the income execution begins, your employer will continue withholding money from each paycheck until either:

The judgment debt, including any accrued interest, is paid in full.

You’re no longer employed there.

Another court order directs them to stop the withholding — for example, an order vacating the judgment or an order from a bankruptcy court.

Anyone you owe money to can qualify as a creditorand attempt to get a judgment and income execution against you. This could include not only debt collectors and credit card companies, but also banks, auto lenders, government agencies, taxing authorities, and even your business partner or spouse. Most types of creditors will need a judgment to garnish your wages. But New York allows wage garnishment without a judgment for some kinds of debts (more on that below).

Wage Garnishment and Independent Contractors

The wage garnishment process only applies to wages. Under New York law, wages are any money an employer pays their employee as part of their employment relationship. In other words, for your income to count as wages, you must be an employee. You can be classified as an employee regardless of whether you work full time or part time and whether you’re paid a salary or an hourly rate. In general, if you receive a W-2 at tax time, you’re probably an employee. If you receive a 1099 instead, you’re probably an independent contractor.

If you’re not classified as an employee, creditors can’t garnish your wages. But they can still collect from you in other ways. For example, a judgment creditor can seize money from your bank account through a bank levy. Bank levies aren’t subject to the same limits as wage garnishments.

Fortunately, though, New York is one of the few states that impose restrictions on consumer bank levies. Under New York’s Exempt Income Protection Act (EIPA), a minimum of $3,000 is protected from creditors. If you have less than $3,000 in your account, creditors can’t access it. The EIPA also requires banks to take extra steps to check whether your account contains exempt income and to make sure no exempt funds are levied. (More about exempt income below.)

A judgment creditor can also seize your personal property and sell it to pay the judgment debt. Or they can put a lien on your real property so that the judgment debt must be paid when you sell the property.

Wage Garnishments That Don’t Need a Court Judgment

New York law gives special treatment to certain types of debts. For these debts, the creditor can garnish your wages without going through the time and expense of filing a lawsuit and getting a judgment. These debts fall primarily into two categories: public debts and family debts.

Public debts include most debts owed to a public or governmental entity. Some examples of public debts include:

Past-due federal income taxes.

Past-due state taxes. This could include state income taxes, property taxes, business taxes, or other taxes owed to the state or local government.

Defaulted federal student loans.

Other fines, fees, or debts owed to the federal, state, or local government.

Family debts include child support, alimony, and related debts. Current child support and alimony obligations aren’t technically debts, but they can be withheld from your pay automatically as part of the support order without a separate garnishment order. Wage garnishments for past-due family support obligations (sometimes called domestic support obligations) also don’t require a separate judgment. These garnishments are also subject to different rules and limits than traditional garnishments.

Upsolve Member Experiences

1,997+ Members OnlineMaximum New York Garnishment Amounts

New York’s laws limiting how much can be garnished from each paycheck closely mirror the federal wage garnishment laws. These limits are based on your weekly income. Here’s how to calculate your weekly pay:

If you’re paid every two weeks, divide your pay by two.

If you’re paid twice per month, such as on the first and fifteenth, divide your pay by 2.17.

If you’re paid once per month, divide your pay by 4.33.

In New York, different garnishment limits apply to different types of debts. To calculate the garnishment limits that apply to you, you’ll need to know:

Your gross income: Your weekly pay before any deductions are taken out.

Your disposable income: Your weekly take-home pay after subtracting mandatory deductions, such as taxes and unemployment insurance.

The minimum wage that applies to you: The minimum wage in New York differs depending on where you live. If you live in New York City, Long Island, or Westchester, it’s $15. If you live anywhere else, it’s $13.20. There are also different rates for tipped service employees and tipped food service workers.

Garnishment Limits for Private Debts

Private debts include any type of debt that doesn’t fall into the public or family debt categories. Credit cards, medical bills, bank loans, and private student loans are examples of private debts.

If your weekly pay is less than the applicable minimum wage multiplied by 30, then your wages can’t be garnished for a private debt. For example, if you’re a librarian in Buffalo who makes less than $396 per week ($13.20 x 30), your wages can’t be garnished. If your weekly pay is more than this, then the maximum weekly garnishment withholding is whichever of these is less:

10% of your gross wages

25% of your disposable income

But, under either calculation, the garnishment amount can’t be so high that you’re left with less than 30 times the applicable minimum wage.

If more than one creditor tries to garnish your wages at a time, usually only the first creditor will actually receive any withholding. This is because the maximum deduction limits apply no matter how many income executions are issued. Typically, the full amount of allowed withholding will go to the first creditor until that debt is paid.

Garnishment Limits for Non-Private Debts

As discussed earlier, public debts — such as tax debt — and family debts, such as past-due child support, are subject to different rules. A creditor doesn’t need a judgment to garnish your wages for these types of debts. Public debts and family debts are also subject to different garnishment limits than private debts.

Family debts include child support, alimony, and spousal support. Although current family support obligations aren’t technically debts, they’re subject to the same maximum withholding limits as private debts.

For past-due family support debts, your employer can withhold up to 60% of your disposable income if you’re not currently supporting any other spouse or children. If you are currently supporting a different spouse and/or child(ren) (not the ones who are owed past-due support), up to 50% of your disposable earnings can be withheld. If the support payments are more than 12 weeks in arrears (past due), an additional 5% of your disposable income can be withheld. This takes the maximum amount of withholding to 65% and 55%, respectively.

Public debts include debts owed to a government or public entity, such as taxes or federal student loans. The U.S. Department of Education can garnish up to 15% of your disposable income for defaulted student loans. This amount is subject to the same cap as private debt withholding — you must be left with at least 30 times the minimum wage each week.

For past-due taxes and other public debts, the garnishment limits depend on the taxing authority or other public entity. These limits are typically based on your income and household size. For example, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) can, in theory, garnish up to 70% of your disposable earnings. This is highly unlikely to happen, though. The IRS uses a complex formula to calculate wage withholding. The amount you need to support yourself and your family and the potential hardship a garnishment would cause you are both factors in the IRS formula.

New York State Wage Garnishment Exemptions

New York law includes a long list of income sources that are exempt, or protected, from being garnished by a creditor. This list doesn’t include ongoing wages, so these exemptions usually won’t affect an income execution issued to your employer (unless you receive one of these income types from your employer). But if a creditor tries to levy your bank account instead of or in addition to garnishing your wages, your account is protected to the extent that it contains money from an exempt source.

Some examples of exempt income sources in New York include:

Payments received from the Social Security Administration or Veterans Affairs

Court-ordered spousal support or child support you receive

Unemployment benefits

Workers’ compensation benefits

Disability benefits

Benefits from public assistance programs

You can view a full list of exempt income sources on the New York State Unified Court System’s website. If your employer receives an income execution and you believe some or all your income is exempt, you can file an exemption claim form with the court that issued the execution. You can usually get this free form from the court.

Job Loss Due to Wage Garnishment

A wage garnishment can happen to just about anyone, so having your wages garnished shouldn’t be a reason for your employer to fire or penalize you. Both federal and New York state laws make it illegal for your employer to fire you, withhold a pay raise, or pass you over for a promotion solely because you have an income execution in place. That said, each wage garnishment requires extra accounting and compliance work for your employer. As a result, these state and federal protections don’t apply if you have more than one income execution.

Bankruptcy and Wage Garnishments

If you file a Chapter 13 bankruptcy, the bankruptcy court can order your employer to send some of your wages to your bankruptcy trustee to fund your Chapter 13 repayment plan. The wage garnishment limits don’t apply to these payments, which aren’t garnishments. Chapter 13 wage withholding isn’t a true garnishment because:

The court and trustee aren’t creditors, and

Withholding for a Chapter 13 repayment plan is a voluntary payment.

Whether Chapter 13 or Chapter 7, a bankruptcy order isn’t the same as a wage garnishment. On the contrary: Filing bankruptcy is one of the only ways to effectively stop a wage garnishment. If you’re dealing with a current or upcoming income execution, it might help to discuss your options with an experienced bankruptcy attorney. If you can’t afford an attorney, legal aid resources may be able to help.

Let’s Summarize…

Most of the time, a creditor must sue you and get a judgment against you to garnish your wages. For some debts, such as family support or past-due taxes, a judgment isn’t required. New York law limits the amount of money your employer must withhold from each paycheck due to garnishment. These limits don’t apply to family support debts or debts owed to public entities.

Your income can’t be garnished if you’re an independent contractor or freelancer or if you make less than the minimum garnishment threshold. Once a garnishment is in place, it continues until you either pay the debt, leave your job, or file bankruptcy.